Closing One Door to Open Another: Saying Goodbye to SwimRVA

From 2019 to 2024, I had the privilege of serving Richmond with access to aquatic wellness programming as a Programs Coordinator, Manager, then Assistant Director for SwimRVA. Below are a few of the invaluable lessons I learned along the way.

Racial and Economic Inequality continue to torment our Community

In 2019 when we launched SwimRVA’s East End program, Oakwood had yet to see the gentrification already happening in Union Hill, Church Hill, and Chimborazo. Many of houses around the Boys and Girls club were crumbling, some abandoned. It was a sleepy neighborhood of longtime residents.

Spending time in the East End of our city opened my eyes. Many days, before I opened the pool, I drove around the neighborhoods where my swimmers lived to build a deeper understanding of their lives: Peter Paul, Fairmount, Woodville, Creighton Court, Fairfield Court, Mosby Court, Whitcomb Court, Fulton Hill, Montrose Heights.

These are the areas of town that I was told to avoid when I was growing up in Richmond, but I saw them now as places that I should become deeply familiar with. How else could I possibly understand the mindset of my swimmers?

Around this time, a friend gifted me a copy of Benjamin Campbell’s book: Richmond’s Unhealed History.

Driving through the East End, I could see his arguments played out clearly.

“At the Core of the city of Richmond…was a cluster of 100,000 citizens whose lives were restricted in ways not unlike those of the underprivileged classes of Virginia’s past.”

“The median household income was below the poverty line, the unemployment rate ranged from 22%-60%, the annual incarceration rate approached 10%, the percentage of out of wedlock births was in excess of 80%.”

“The children went to schools that were more racially segregated than they been in 1970, which were now also segregated not only by race, but also income.”

“Ninety percent of the students were eligible for free or reduced lunch, and more than 90% were African American.”

“In the three most distressed high schools, one quarter of the student body did not graduate on time.”

“Within this district lay every public housing unit constructed in Metropolitan Richmond, with few daycare centers available for childcare.”

I share this narrative of the East End not to disparage the residents who live there, and not because I am the first to make these observations, but because I believe most of the White people I know are either naive, or in denial of reality. For those who do not often spend time in this part of the city, it is impossible to truly understand the scope of how much disparity still exists in our community in 2024.

Recently a white friend who lives in a wealthy part of town commented to me that “Richmond isn’t a very Black city”.

To me it was a shocking, but classic example of how truly separated our community is still. People who live out of sight can easily slip out of mind.

According to the 2022 Federal Census, Richmond’s population is 44% Black - the same percentage of Richmonders are White. So how could anyone think that “Richmond isn’t a very Black city”?

Because to this day we live and work in dejure racially segregated communities.

Because racial and economic inequality does not get the mainstream attention that it should.

If you’re not convinced, this 2021 Brookings Institute study on “place-based discrimination” makes it painfully clear:

We have a lot of work to do in Richmond.

Swimming as a Metaphor for Life

Teaching people to swim is just like teaching people to practice yoga.

There is so much emotional baggage that has to be released in order to find that “flow state”.

Water is a key part of our existence, one of the five major elements of nature. I often say that a person’s relationship to water says a lot about their state of mind. Do they float and glide with ease, trusting their body to move them to safety? Or do they tense and struggle against water in fear?

Before working for SwimRVA, I had about six years of experience under my belt as a swim instructor.

But I never before worked with a population so touched by social injustice that they held an innate fear of water in their tissues.

Generational Trauma is absolutely real. It is pervasive and harmful and must be healed for us to move forward.

Teaching swimming in the East End often brought me into contact with entire families who never learned to swim. Grandparents who were denied access to public swimming pools in the 1960s taught their children to fear the water, who in turn taught their children that water was synonymous with “drowning to death”. Numerous children shared with me that members of their families had died by drowning.

This is yet another symptom of our broken and racially inequitable social system playing out before our eyes.

According to the American Red Cross[1]:

“64% of African American children do not know how to swim”

“When parents have no or low swimming skills, their children are unlikely to have proficient swimming skills. This affects 78% of African-American children.”

“African American children ages 5-19 drown at rates 5.5 times higher than white children of the same age range.”

Is it any wonder why our swimmers came to the pool rigid with apprehension and fear?

When humans are scared, their minds go into a sympathetic nervous system response, often called “fight or flight”. In many cases this can also be described as a “trauma response”. When we enter a “fight or flight” mindset, our muscles surge with adrenaline, we become rigid with anticipation and overly reactive to unfamiliar stimuli. It is nearly impossible to learn anything in this type of mindset, because we are focused on survival.

Many of our East End swimmers were locked into this “fight or flight” nervous system response all day long as a result of experiences like: hunger, gun violence in their neighborhoods, household economic distress, abusive domestic relationships, etc. In order to teach them to swim, we needed first to bring them back into a parasympathetic nervous system response, often called the “rest and digest” state of mind.

This is accomplished by exhibiting that the pool area was a safe place, earning their trust through deep listening and upholding promises, allowing them to try things at their own pace, and using relaxation tools like deep breathing. All of these strategies parallel the ways that a yoga instructor introduces beginning students to the yoga practice.

For me, teaching swimming became and extension of my role as a yoga instructor. Teaching swimmers to self-regulate in order to grow from new experiences is teaching a form of yoga in itself.

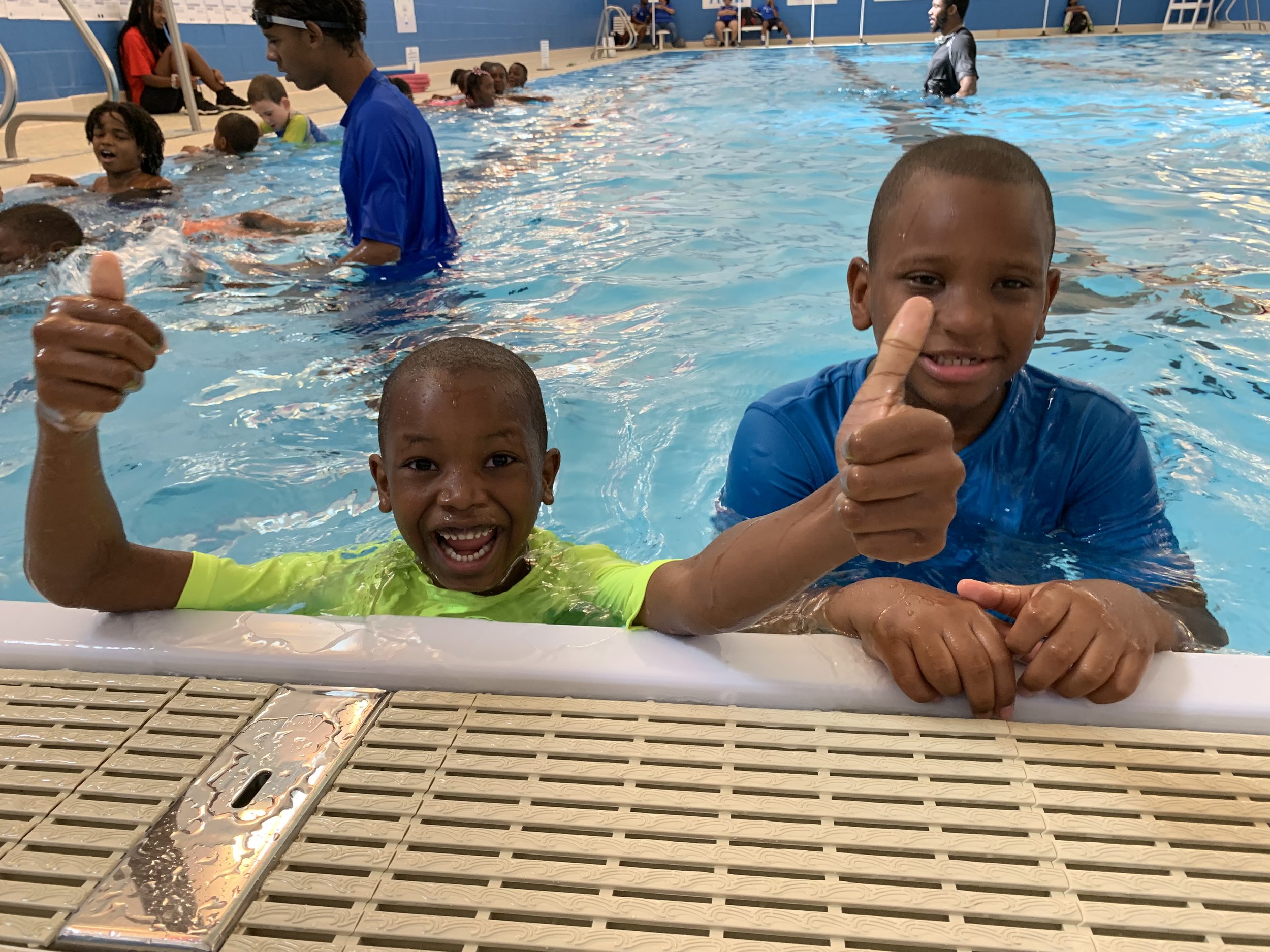

I watched this practice of self-regulation help many people learn to swim - more than 1,000 learners per year. And as they released their anxieties in the pool, they learned to use the same strategies to cope with challenges outside of the pool.

Learning to overcome fear of the water helps people grow into more resilient, confident, and bombastic versions of themselves.

Each of Us has a Part to play in shaping the Future

“What kind of ancestors does the future need from us?”

This quote has rattled in my brain since I heard it, and made me consider what I can do to make this world a better place for the people who come after me. When I think about the future of humanity, it’s hard not to slip into grief. Many days I feel that I am witnessing the downfall of man: people bickering and denying each other basic rights, while our environment collapses around us - brought on by our own greed and denial.

But I want to live in a better society, and I choose to work in hope for the total liberation of all people. For this reason I ask myself:

How can I leverage who I am, what I have, and who I know to deconstruct systems of oppression?

Teaching people to swim in the East End forced me to unpack my privilege as a White woman. It challenged me to level with, and release the “white savior” mentality. It taught me that even in my smallness and insignificance to the bigger picture of societal injustice, my daily work could make a positive impact in peoples’ lives.

I could pour my heart and soul into my swimmers and staff, showing up for them in ways that made them feel seen, heard, and loved.

I could work actively to create images and symbols of Racial Representation in the pool area (i.e. sourcing Black mermaid dolls and posting photos of Black Olympic swimmers).

I can pressure White leaders to use their proximity to power and wealth to increase access and opportunity for marginalized peoples.

I can use my voice and my platform to spread awareness and understanding amongst my social circle, which they can spread outward.

Each of us has Choice in how we face systemic oppression:

Will we hide our heads in the sand, or stand up for what we believe to be right and just?

Will we choose to act consciously as we move about in the world, making decisions that benefit the collective?

No person is too small to make ripples. And if we work together we can make great waves of change. This realization helped me to move past notions of shame and guilt, and instead find Purpose in helping to heal others.

And in working to heal others, I found healing within myself.

For this reason, I believe we should all seek to heal our individual relationships with the injustices of the past and present.

In working to uplift those most in need, it will help us to heal as a collective, and raise the vibrations of our society.

When in Doubt, Listen

Deep Listening will change your relationships, and by extension, your life.

The most valuable aspect of my time at SwimRVA has been the wisdom I gleaned by listening: to my students, my leaders, community members, and to the personal feedback shared with me.

When we re-opened the East End pool in 2019, I was literally the new kid on the block. The Salvation Army Boys and Girls Club had been in operation for more than 50 years. The building underwent a massive renovation in 2018 thanks to several million dollars donated by a handful of community movers and shakers. SwimRVA was awarded the pool management contract, and by extension, jurisdiction of all programming in the pool. In the early days there were deep feelings of distrust that an outside organization (of White people) could come in to the Club, based solely on the decisions made by the donors.

So I made it my priority to build relationships with the tenured staff in the Boys and Girls Club. Every day I spent time small-talking and getting to know them, asking questions and volunteering any information about our programs that they wanted to know. I built and open-door policy, always inviting the Club staff to join me on the pool deck and feel comfortable in the pool office. I shared with them my personal cell number and encouraged them to contact me with any concerns they may have. I showed up with vulnerability, sharing my personal struggles and dreams. I invested time and energy into listening to them.

Over time my relationships with the Club staff blossomed, and work partnerships grew into friendships that shifted my perspectives and my priorities.

Several of the Club staff grew up in Oakwood, went to the Armstrong High School (back when it was called Kennedy) and have worked in the Club for decades. They shared with me stories about the neighborhood, about the history of the Club, and memories of how public swimming pools were not available to them growing up. They taught me more about Oakwood than I could ever have learned in any book or archive. They treated me with dignity and respect, and propped me up on days when I was emotionally exhausted by the work.

When I was hospitalized in 2022, the Club staff sent me flowers and cards with messages of hope and support. These messages live on my desk to this day, keeping my head and my heart in the right place.

And then there were my staff: mostly neighborhood teenagers and a few quirky adults, all of them unique and special to me in their own ways. Through the toughest days of programming chaos and pool malfunctions, they stayed dedicated to our mission, inspiring me to weather the storms. In moments when I put my foot in my mouth during sensitive conversations, they gave me feedback on how I could do better. One such conversation led to a breakthrough of understanding for me and a moment of major personal growth.

I would absolutely not be the person I am today without each of the people I shared space with in the East End. I will forever be grateful for my time running the pool at SwimRVA - Church Hill and will forever support the mission to drownproof Richmond.

Lifelong Fitness Matters, for All People

When SwimRVA re-opened the pools after the COVID shutdown in 2020, I absorbed management of the Health and Wellness program. Focused primarily on Seniors, this program boasts 15 fitness instructors and serves the community with 70 group fitness classes per week.

After years focused on youth programming, the Seniors challenged me to rethink how I defined “fitness”. I grew to see fitness not just an opportunity for their lifelong participation, but also their their lifelong employment. All of the fitness staff I managed were older than me by decades, some of them more than double my age. Their deeply held opinions, and willingness to loudly voice those opinions, helped me find patience I never knew I could possess.

Running senior wellness programming taught me to approach programming from an “all ages” perspective and address disability in new ways. This program also gave me the opportunity to grow skills in event planning and management. When I adopted the program in June 2020, participation was at an all time low due to COVID concerns.

For three years, we worked to rebuild engagement through monthly educational events, personal coaching sessions, and a large scale Community Wellness Fair. By the end of 2023 participation had returned to pre-COVID levels.

My favorite aspect of running the Health and Wellness Program were the one-on-one Wellness Consultations offered to participants. Taking time to sit down with folks, assess their physical and mental well-being, and build personalized exercise plans was rewarding. Many participants opened up to me about deeply personal struggles. Helping people overcome feelings of shame and guilt surrounding inactivity emphasized how important it is for everyone to have access to fitness opportunities.

Physical Inactivity is an epidemic in our country, particularly for folks in social and economic disadvantage. Whether in the pool, or on land, all people NEED access to some type of physical activity. But in addition to access, there needs to be a sense of belonging. If they don’t feel like they belong, they won’t come back. Fostering social connections in a fitness setting was a keystone focus of mine, and one that I hope is continued in my absence.

Where To from Here?

As I enter the next chapter of my career, it’s impossible for me to not feel deep nostalgia for where I have been. Change is hard, particularly when you love what you do. There are many things I will miss about working for SwimRVA, especially the team of passionate coworkers who surrounded me.

I will miss the smiling faces of children enjoying their first ever swim lesson. I will miss the sounds of laughter emanating from Lawrence’s shallow water fitness classes. I will miss watching the swim team crank through massive swim practices, moving through the water with such ease and grace.

But after my experience in 2022 I have been feeling called to use my voice to increase public support for and access to bike and pedestrian infrastructure in our community.

I am excited to continue the work of creating accessible wellness experiences as the Special Events and Program Manager for the Virginia Capital Trail Foundation starting in January 2024.

So in the spirit of changing lives through recreation, I shout: